Date: 9th October 1957

Venue: The Midland Hotel, Birmingham

Sponsor: Walter W. Hoffman

Minutes of an American Thanksgiving Dinner

An “American Thanksgiving Dinner” was held at the Midland Hotel, Birmingham on October 9th, 1957. The rules of the Club prevented its being held on Thanksgiving Day, November 28th.

The sponsor was Mr. Walter W. Hoffman, American Consul in Birmingham and a member of the Club. The only guest of the Club was Mr. Donald W. Smith, United States Counsellor of Embassy and Consul General in Britain.

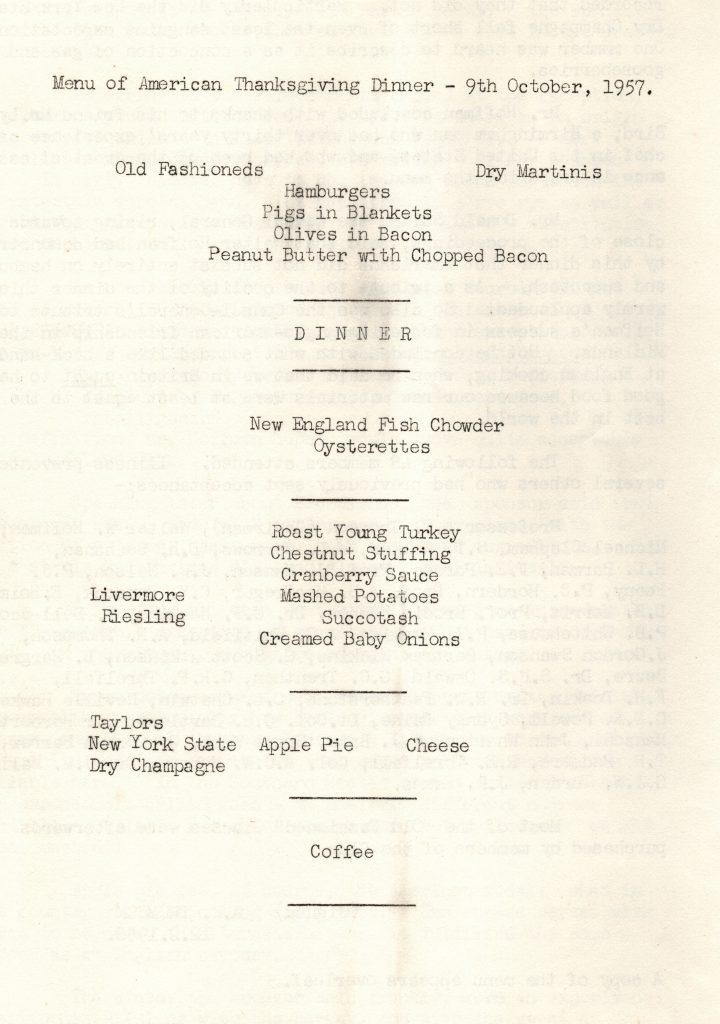

At the reception members’ appetites were sharpened – or blunted, as the case may be – by the selections of Hamburgers, Olives in Bacon, Pigs in Blankets and the like. The satisfying effects of these tasty morsels, consumed in series, were offset by Old Fashioned cocktails, served in appropriate tumblers which the Club had purchased for this occasion. The less adventurous, however, were permitted the alternative of Dry Martinis – the American version and not, as the sponsor put it, “what passes for a Dry Martini in Britain”.

The dinner itself was sustaining rather than exotic. Early in its course the Chairman welcomed the Consul General warmly and took occasion to empress the Club’s valedictory good wishes to the sponsor, who was due to leave Birmingham and retire from the Foreign Service of the United States at the end of the year.

The Chairman observed that we were indeed dining both historically and geographically. The menu card quoted at length a passage from Governor Bradford’s‘ History of Plymouth Plantation”, recording the great drought of the year 1623 and its ultimate breaking in such time and degree as to save the harvest, “for which mercie, in time conveniente“, Governor Bradford wrote, “they also sett aparte a day of thanksgiving“.

The sponsor began his remarks with the comment that the privilege of sponsoring a Buckland Club dinner seemed to be the apogee of the career of an American Consul in Birmingham. His predecessor Phil Hubbard had planned but, unfortunately, could not remain here long enough to partake of this honour. He (Mr.Hoffman) was more fortunate. He hoped members would enjoy the meal as much as he had enjoyed sponsoring it. He only regretted that this would be the last time he could savour the delights of those pleasant and highly rewarding occasions.

He felt obliged to point out that the name given to the dinner was something of a misnomen (sic). Thanksgiving in America was a family holiday at which all, both old and young, participated and so the liquid fare was not offered on quite the same scale as that night. A Thanksgiving Dinner was generally toned down to the tastes and needs of the youngest participants, The sponsor hoped the Club would accept this as having been done in the present instance also.

Referring to the refreshments served at the reception, the sponsor agreed that the cocktail habit is American in origin – an import for which no dollar licence was required. A more typically American drink, however, was whisky – either bourbon or rye. In early colonial days it was the one drink for which the raw materials were at hand. He had hoped to serve rye as well as bourbon, but insuperable obstacles had compelled the substitution of Dry Martinis.

As for the Old Fashioneds, made with bourbon, he had tried to ascertain the origin of the name. Reference to Webster, the standard American dictionary, shed no light except insofar as it gave the following definition of the word old-fashioned:

“Characterised by behavior, manner, etc., befitting adults; having mature ways; hence precocious, intelligent.”

This definition, Mr. Hoffman hoped, would prove quite acceptable to the Buckland Club.

Speaking later about the dishes, the Sponsor said that Chowder was a soup made with either cod-fish or clams, with the addition of potatoes, salt pork, milk and other ingredients. It was a staple New England dish and almost a meal in itself.

Speaking later about the dishes, the Sponsor said that Chowder was a soup made with either cod-fish or clams, with the addition of potatoes, salt pork, milk and other ingredients. It was a staple New England dish and almost a meal in itself.

Turkey and all that went with it needed no introduction, with the possible exception of succotash. That name was of Indian origin and was given to a mixture of maize and beans.

Sweet potatoes were well known in parts of the British Commonwealth, particularly New Zealand, where they were called Kumaras, and also in the West Indies. It was due to the influx of West Indians into Birmingham that sweet potatoes had become available here. In the Southern States of the United States they were erroneously called yams – an entirely different coarser vegetable. Alas! our sweet potato merchant failed us: we had to eat mashed.

Apple pie was, of course, the American model: what in this country would be called apple tart. The cheese served with it was to be eaten in alternate bites; it fulfilled the same purpose as an English savoury.

The wines, the sponsor said frankly, were an experiment; a California Riesling with the turkey, and with the sweet a Champagne grown and made in New York State. American Vintners, he added, made great claims for their products, and he sincerely hoped members would find these claims justified. It must be recorded that they did not. Particularly did the New York State Dry Champagne fall short of even the least sanguine expectations. One member was heard to describe it as a concoction of gas and gooseberries.

Mr. Hoffman concluded with thanks to his friend Mr. Lyndon Bird, a Birmingham man who had over thirty years’ experience as a chef in the United States, and who had been of the greatest assistance in preparing the menu.

Mr. Donald Smith, the Consul General, rising towards the close of the proceedings, said that Walter Hoffman had demonstrated by this dinner that Americans did not subsist entirely on hamburgers and succotash. As a tribute to the quality of the dinner this was warmly applauded. So also was the Consul-General’s tribute to Hoffman’s success in fostering Anglo-American friendship in the Midlands. But he concluded with what sounded like a back-hander at English cooking, when he said that we in Britain ought to have good food because our raw materials were at least equal to the best in the world.