Date; 12th February 1958

Venue; The Midland Hotel, Birmingham

Sponsor: Hamilton Ellis

Minutes of a Railway Dinner

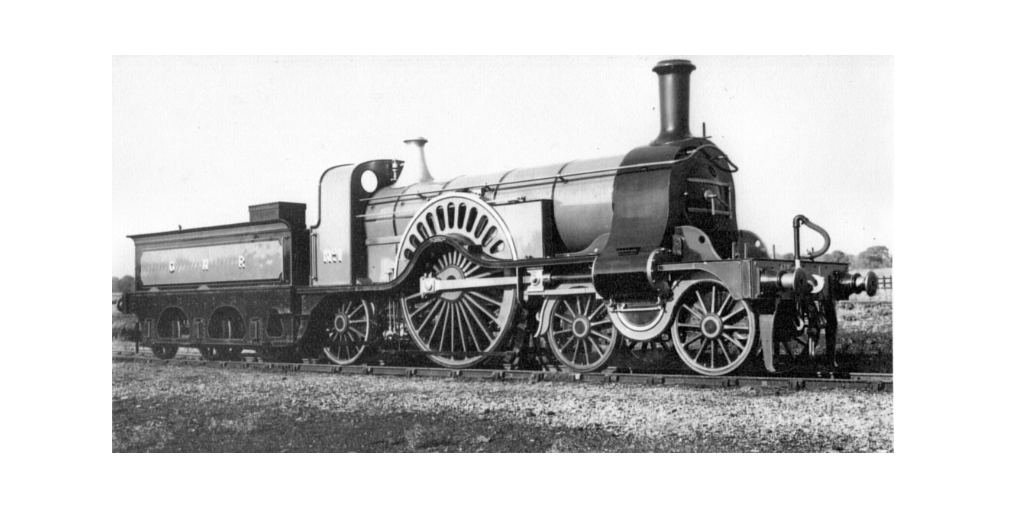

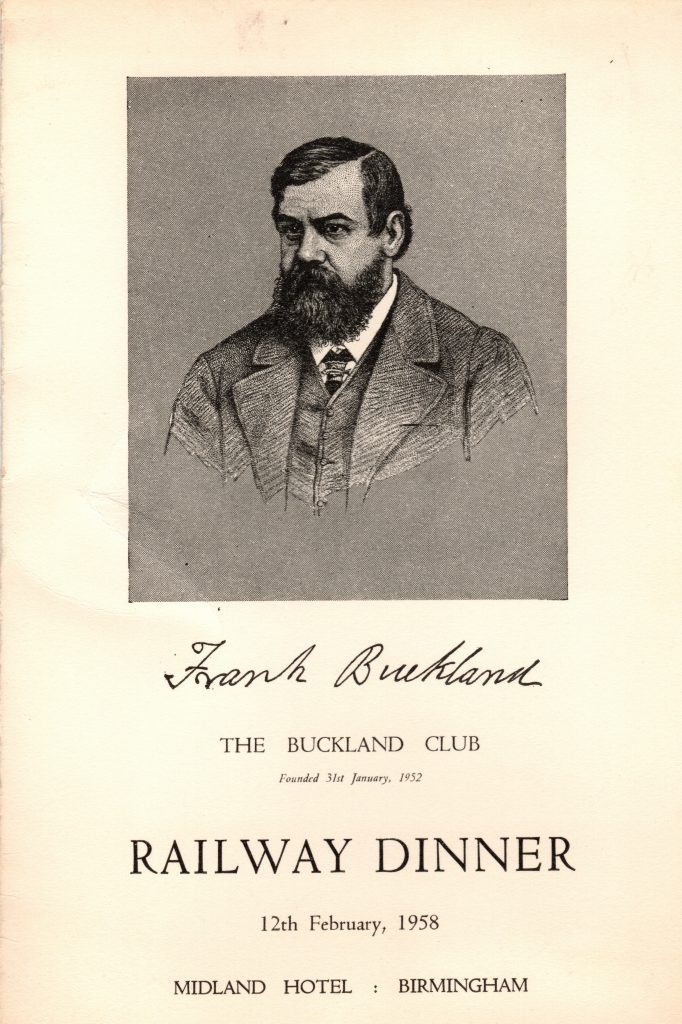

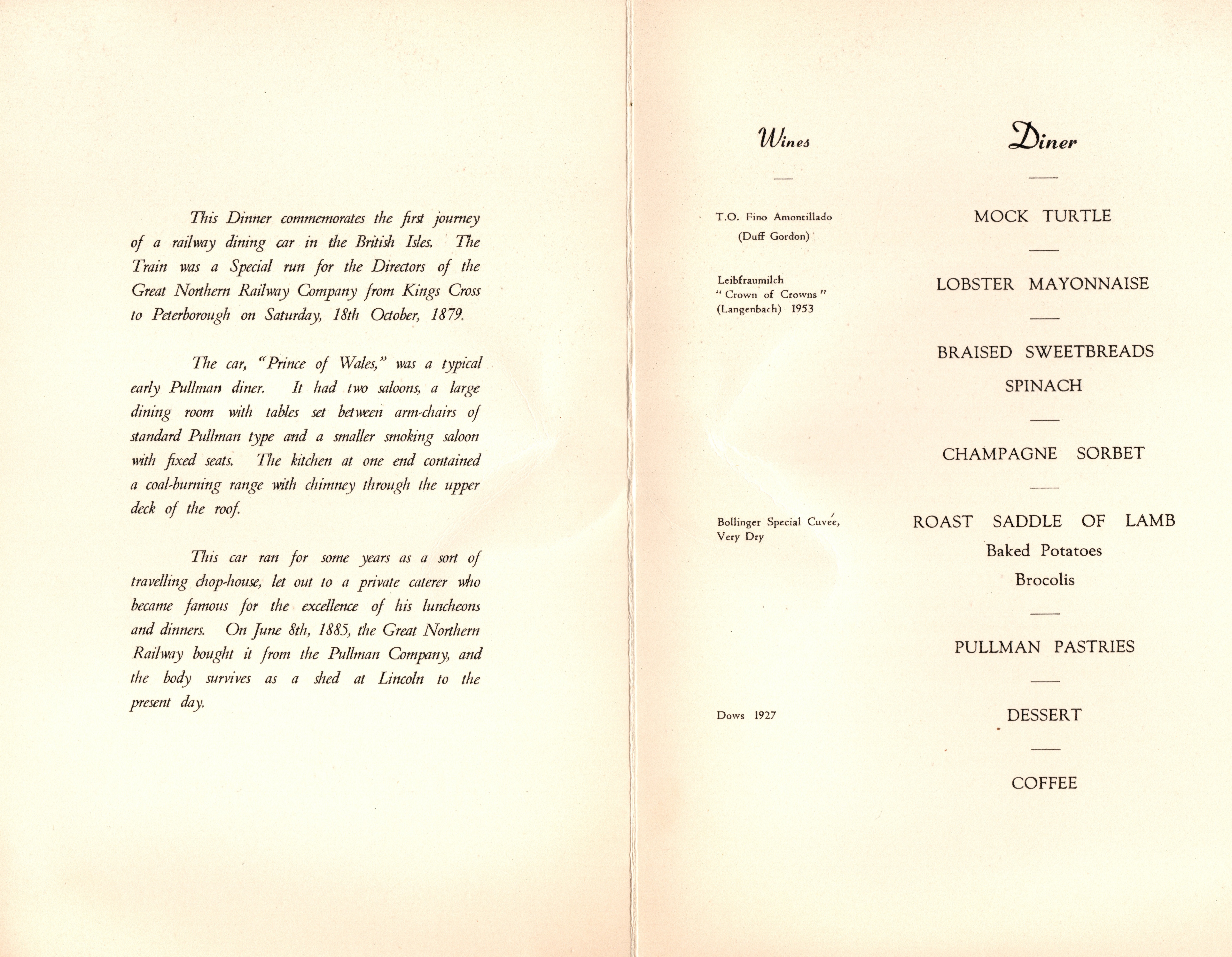

For its Spring dinner of 1958 the Club reproduced so far as possible the first meal served on an English railway journey: not the ordinary meal, however, provided for the public, but the directors’ feast of six courses inaugurating the service of the Pullman Palace Car Company on the Great Northern Railway between King’s Cross and Leeds. This special train ran from King’ s Cross to Peterborough on October 18th, l879, covering the 76 miles in about 90 minutes.

The guests of the Club, all railway enthusiasts, were the Earl of Northesk, Chairman of the Talyllyn Railway, and Messrs. C. Hamilton Ellis, railway historian, G.S. Cattell and W.J.B. Walker.

At the reception, thanks to P.B. Whitehouse and G.S. Cattell, members saw a very impressive exhibition of early railway pictures and relics, including the coats of arms of many lines, big and little, and a watercolour of the actual Pullman car ”Prince of Wales” in which in imagination the Club was dining that night. ‘

The sponsor was Mr. Hamilton Ellis, who had travelled from Brighton for the occasion – so punctually that he arrived at New Street by a train an hour earlier than that on the schedule with which he had supplied the Hon. Secretary.

At the table the Chairman, though certainly not all at sea, in one respect resembled the Bellman in “The Hunting of the Snark”: only more so, because he had two bells with which to announce events, one an old North Staffs. Railway bell, the other an Inverness and Aberdeen.

In welcoming the guests one by one, the Chairman confessed himself in difficulty, since Frank Buckland had no high opinion of railways. He extricated himself with a sustained ingenuity so intricate that particulars of the feat escaped the Hon. Secretary’ s after-dinner memory. Perhaps like the mechanism of the fishing reel according to Izaak Walton, it was better followed by personal observation “than by a large demonstration of words”

Commenting discursively between courses, Mr. Hamilton Ellis said that Frank Buckland was a greater man than any the transport industry had yet produced. He himself read Buckland’s life when a boy and resolved to grow a beard. Members noted that he had persisted in that boyish resolution and – that he had still some way to go.

The sponsor recalled Buckland’s arrival at Charing Cross Station with a monkey on his arm. The ticket collector demanded a ticket for the monkey “because a monkey’s a dog”. When Buckland also produced a tortoise, the inspector decided: “A tortoise is an insect – no charge “.

The sponsor held up to the Club’s admiration a passenger on the early London and Birmingham line who left the train at Wolverton and bought a pork pie and a pint of stout, declaring that he didn’t permit his stomach to dictate to him. That was in 1839, before the days of restaurant cars. The first meals in the world to be served on a train were on the Great Western Railway of Canada in 1867, the car being both diner and sleeper. The meal which the Club was commemorating was cooked as well as served in a Pullman car that had been prefabricated and shipped here from the United States.

The sponsor raised without settling the question why British railway meals were so unexceptionably vile compared with the exquisite meals on French railways. He went so far, though, as to claim that ours were not the worst in the world. One of the best he had eaten on a British train was served on the Royal Highlander, when his fellow passengers included an Australian touring cricket team and the Maharaja of Nepal, whose entourage cooked rice on the floor of a sleeper. Members were left uncertain whether this best-ever railway meal was the rice .

The commentary ranged from railways to grasshoppers and from history to personal reminiscence – with a bias to reminiscence. Finally the sponsor recalled a long journey on the Trans-Siberian Railway, when the train was held up until a bear arrived on a sledge. Next day the bear was served for lunch.

The only Russian touch that night on the Club’s menu was the Russian cigarettes served with the sorbet. Perhaps the hotel management supposed that our imaginary destination was Petersburg, not Peterborough. .

At the sweet course, described as ”Pullman Pastries”, an imposing model of a railway train in multi-coloured sugar was borne in ceremoniously and placed before the Chairman amid loud applause. It was the work of many days created by the hotel’s confectionery chef, Mr. H. Arens. The model was afterwards presented to the Children’s Hospital, where it presumably came to a sticky end.

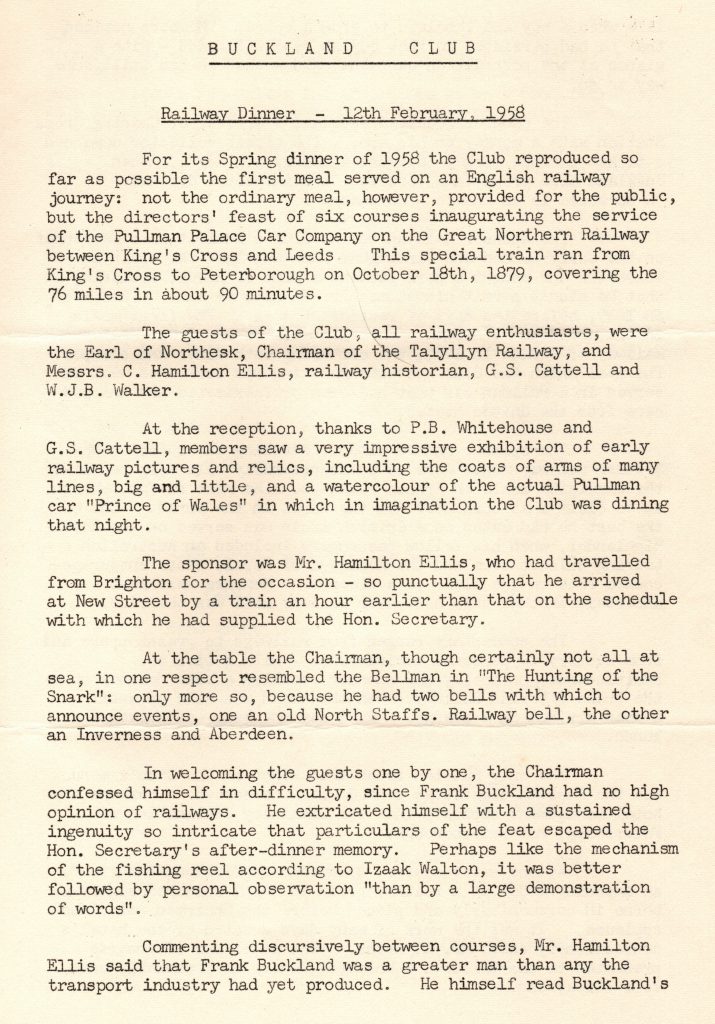

At dessert the Chairman invited Lord Northesk to address the Club. His speech made a delightful close to the dinner. He said that not only was he Chairman of one of the few railways still outside nationalisation but had qualified in turn as fireman and driver and so claimed to be a true railwayman.

As a lover of the old Great Northern he paid tribute to the accuracy of the sugar model train with its 2-2-2 Stirling express locomotive – far and away the best work of its kind he had ever seen. That fidelity to detail evidently epitomised the spirit of the Buckland Club.

…54 members attended.

A.P. Thomson

8th October 1958