Date: 24th February 1960

Venue: The Midland Hotel

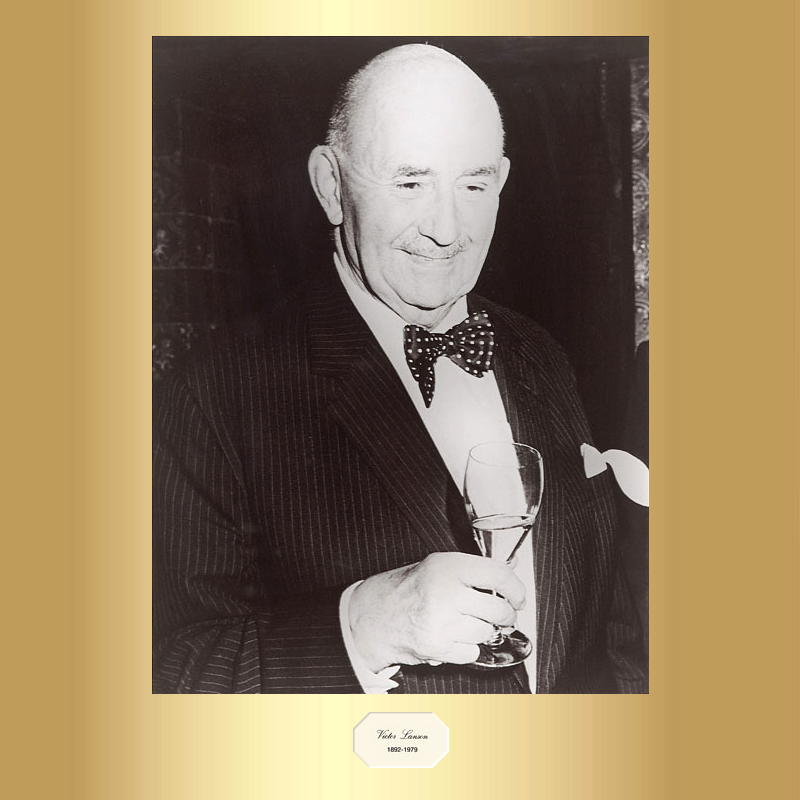

Sponsor: Mons. Victor Lanson

Minutes of A Champagne Dinner

On February 24th, 1960, a Champagne Dinner was held at the Midand Hotel, Birmingham. This was one of the Club’s greatest occasions. It was subsequently accorded favourable notice in “Harper’s Wine & Spirit Gazette”. Members showed their hopes by attending in unprecedented strength.

The Club’s guests were Mons. Victor Lanson*, head of the celebrated Rheims firm, Mr. J .C. Ionides, the Consul for France in Birmlngham (Mons. G. de Coulhac—Mazerieux) and Dr. F.G. Healey.

At the reception, after other aperitifs, a glass of non-Vintage champagne was served.

Presiding at the dinner, Sir Arthur Thomson welcomed the guests individually. For the arrangements the Club was much indebted to Bertram Wickins and Denis Morris**, who reported his file of the dinner was 9 inches thick, but above all to the sponsor, M. Lanson, who had come to Birmingham especially for the occasion.  His firm had just celebrated its 200th anniversary. As part of the bi-centenary celebrations M. Lanson himself, though not far from 70, was trotting the globe and taking the Club in his trot. It would have been less than grateful to him if these minutes had not been unusually full. In order to curtail their length, they have been limited, however regrettably, almost entirely to his own remarks.

His firm had just celebrated its 200th anniversary. As part of the bi-centenary celebrations M. Lanson himself, though not far from 70, was trotting the globe and taking the Club in his trot. It would have been less than grateful to him if these minutes had not been unusually full. In order to curtail their length, they have been limited, however regrettably, almost entirely to his own remarks.

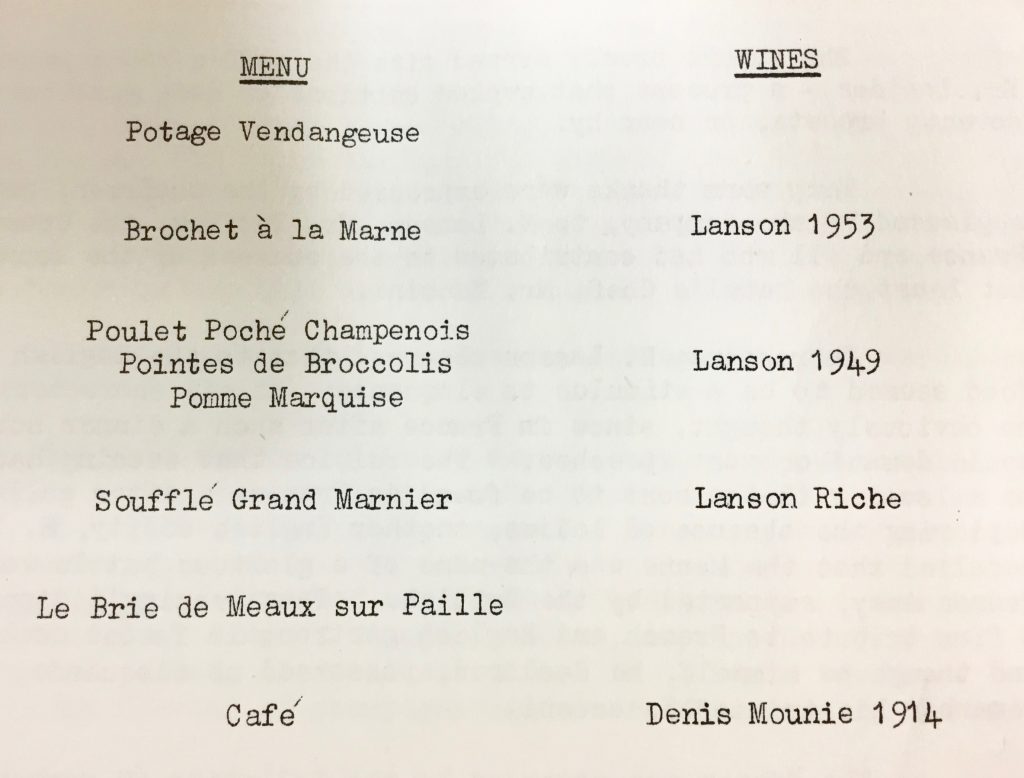

For accuracy it had been decided to style this a Champagne rather than a Marne Dinner. Champagne was served with every course, but with each course a different champagne. The difficulty was to accompany the wines with worthy dishes. It was overcome by cooking them in champagne.

In his comments between courses, the sponsor said that when he was asked what were possible dishes for a Champagne Dinner, his first answer was only poor stuff – nothing worthy of a menu to offer amateurs of good food. ”You must know”, he said, “that until the 18th century, vines were grown on the side of the hills of the Champagne area. The flat country was dry: sheeps and wild rabbits were the only animals for cooking. Many people don’t appreciate wild rabbits, and the meat from our sheeps was rather stuffy: the wool excellent but, as you know, not for cooking”.

It may be remarked in parenthesis that the sponsor would have been shocked to learn that the barbaric English do, or used to drink “Lamb’s Wool”, a concoction prepared with hot beer, sugared, spiced with nutmegs and with roasted apples floating thereon. This was no occasion to tell him.

The usual food of the farmers of the Champagne region, he said was a Cabbage Soup. The old receipt was simple: water, salted bacon, potatoes, cabbages. It could be boiled slowly on the side of the fire while the farmers were working in the fields. The soup was used for lunch; the bacon was kept for dinner, cold with salad. But recently that soup had been improved. He knew an old woman who, when asked about her excellent soup, would reply: “It is very easy: you put too much of everything, not much water, and boil it slowly six hours”, but she forgot to say that she added a handful of corn-pepper.

Members agreed that somehow the Cabbage Soup had been much improved.

Members agreed that somehow the Cabbage Soup had been much improved.

The fish was Brochet à la Marne – otherwise pike boiled in Champagne. Was there ever such pike? From the small rivers of the district, the sponsor said, where the water runs very clear and cold, the pikes are very good to eat. To-night‘s were cooked but not boiled in court bouillon. The chef had first boiled ¾ parts of champagne, ¼ of water, one glass of good vinegar, onions, carrots and pepper. When the liquid had cooled, the pike was placed in it for a few hours before cooking. The flavour of champagne had entered the fish. (It had indeed!)

The next course was Poulet au.Champagne. “First”, M. Lanson emphasised, “to pick the right chicken”. The quality of chickens, as of wines, differs district by district. “Don’t speak of those artificially fed specimens which I call ‘nylon chicken’. Any way you try to cook them, their taste is poor“. To-night with the help of champagne in the sauce, mushrooms and truffles, the Chef, he declared, had produced the masterpiece of this memorable dinner – together, he believed, with the sweet soufflé which was to come. He congratulated the Chef for the great art he had shown that night: how wrong it would be to say on this occasion that the Devil had invented the Cook.

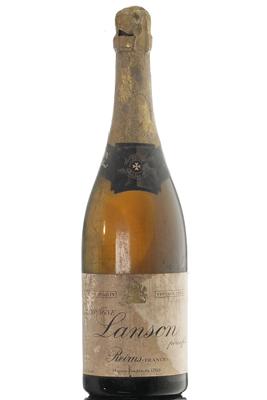

The wines served with the courses were: with the fish, Lanson 1953; with the chicken, Lanson 1949, a great wine; with the soufflé, Lanson Riche, a wine little known in our country, which was the generous personal gift of the sponsor to the Club.

The wines served with the courses were: with the fish, Lanson 1953; with the chicken, Lanson 1949, a great wine; with the soufflé, Lanson Riche, a wine little known in our country, which was the generous personal gift of the sponsor to the Club.

‘While waiting for the soufflé, “perhaps as long as we have to wait for our ladies”, M. Lanson said reminiscently, he took opportunity to discuss the 1959 vintage, that year of four months continuous sunshine – too much sun! But his personal forecast was that 1959 will have yielded some marvellous wines of astonishing quality, which he invited members who happened to come to Rheims to join him in sampling.

M. Lanson recalled incidents in his firms 200 years, notably the early days of bottling champagne; the disasters apt to occur in fermentation; would the wine be sparkling or would nothing have happened? Bottles might burst by the thousand, or leak in days before ccrk superseded rag. The most important thing that ever happened to the champagne industry was the knowledge contributed by Pasteur.

The superb brandy served with the coffee was a present from Mr. Ionides – a present that evoked emotions of deep gratitude in seventy breasts, or near by. Very warm thanks were expressed by the chairman and loudly applauded by the company, to M. Lanson, Mr. Ionides, the Consul for France and all who had contributed to the success of the occasion, not least the hotel’s Chef, Mr. Mancini.

In response M. Lanson observed that to the English good food seemed to be a stimulus to eloquence: an odd characteristic, he obviously thought, since in France after such a dinner nobody would demand or want speeches. The cuisine that evening had been on a level wlth the best to be found in France. After gallantly deploring the absence of ladies, another English oddity, M. Lanson recalled that the Marne was the name of a glorious battle won by the French Army, supported by the British. That evening’s dinner was a fine tribute to French and English gastronomic forces combined. And though he himself, he declared, possessed no eloquence, we should remember his inimitable accent.

The dinner was attended by 62 members.

-oOo-

Further insight on the evening’s Sponsor (taken from Lanson’s website)

https://www.lanson.com/en/the-house/

* Victor Lanson then took the helm (of Lanson) in 1928. He had a considerable influence on the House’s history, and would become known as the “great ambassador of Champagne”.

In 1937, he wanted to promote sales of non-vintage dry wine and decided to name the blend Black Label in honour of the House’s biggest market, Great Britain. He was also one of the first to develop rosé champagne.

Etienne Lanson, one of Victor’s sons, joined the House alongside his father. He took over in 1967 and decided to conserve vintages in the cellars to develop a unique wine library, from which the House still benefits today.

-oOo-

Background to the Dinner

**Denis Morris spent 20 years as wine correspondent of The Daily Telegraph. However, some years beforehand, he took a three month sabbatical from the BBC (for whom he was a programme director in Birmingham). During this period he travelled 5,000 miles through France with his wife. The result was his second book – The French Vineyards (Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1958).

Committee members have historically thrown themselves, with passion and dedication, into researching Buckland Club dinners.The passage below, from Chapter 2, Champagne: Golden & Bubbling with Pride, demonstrates the link between the Club and The House of Lanson, as well as providing a guide as to how to maximise the enjoyment of this most classic of wines:

We arrived in Reims at midday instead of the later afternoon and happened to meet our host, Etienne Lanson, in the street outside his home. He told us that he was on his way to vote, which seems a very civilized thing to be doing on a Sunday, instead of trying to run it in before or after going to work, as we do.

Etienne’s father, Victor Lanson, knew that we were going to spend several days visiting a very representative number of champagne makers and had oflered us a room above the offices of Lanson Pére et Fils as a ‘pied à terre’. The room turned out to be a delightful flat which contained two particular treasures.

One, the caretaker-cum-general-handyman of the firm, dubbed Jeeves, who turned out to be a kind, friendly man – a constant car polisher and trouser presser. The other, a large ice box just by the door.

‘Whilst you are here’, said Etienne, ‘you will be drinking a lot of different makes of champagne; It is essential for you to have a yardstick. Here it is.’ And with that he opened the door of the cupboard to show us rows of Lanson 1949, 1947, and Black Label, in bottles and half bottles.

In a few minutes we were already drinking in our first lesson. Champagne should always be served cold, but not too cold, at about 44 to 48 degrees -colder, it will lose its flavour and fragrance; warmer, its sparkle becomes a rushing torrent – a real vin du diable as it was formerly called, before the Monk Dom Pérignon and chemists like Pasteur came to master its turbulence. We also learnt how bad the flat, cut-glass champagne tumblers, that get handed from one generation of the thriven to another are for the wine. It takes some five years to make a high-grade champagne, and much of the time and trouble in its making is taken up by conserving the bubbles for the great moment. The wide area exposed to the air in a large open glass enables the bubbles to escape far too quickly, with the result that the second half of each glass is comparatively flat.

Most champagne makers are convinced the right glass is a tulip-shaped one, and also that the glass should never be allowed to become quite empty until the wine is finished. If you do this the delicate bubbles that give champagne its refreshing pick-me-up,isn’t-the-world-a-wonderful-place-and-aren’t-I-lucky-to-be-married-to-you kind of quality will go on all the time. At least it will if you have had the wisdom or luck to be drinking your wine out of a glass that has been dried with a linen cloth after washing up-cotton is death to the wine.

All this we learnt as we sat drinking our first bottle of Black Label, and we learnt too how different it makes the world feel even when you are very tired on a wet spring morning.