Date: 24th February 1965

Venue: The Midland Hotel, Birmingham

Sponsor: Professor Ellis Waterhouse, C.B.E.

Minutes of a Florentine Renaissance Dinner

On 24th February 1965, at the Midland Hotel, Birmingham, the event was a Florentine Renaissance Dinner: in fact, more Renaissance than Florentine, as was emphasised by the sponsor, Professor Ellis Waterhouse, C.B.E., Director of the Barber Institute, University of Birmingham. At the reception a white Chianti was served.

The Chairman, Sir Arthur Thomson, announced apologies from the Vice Chairman, Professor Frazer, Mr. R.S. King-Farlow and Mr. Brian Vessy-FitzGerald, one of the Associate Members, who had made all arrangements to travel from Surrey when illness overtook hlm. Another Associate Member made the journey from Wiltshire – Brigadier Frank Backland. Fifty-six members were present.

The chairman welcomed the Club’s guests: Professor E.K. Waterhouse, Mr. E. Piccioni, Italian Vice-Consul in Birmingham, Mr. E.H.W. Atkinson, London Editor of The Birmingham Post and Mr. A.H. Westwood, Master of the Assay Office, the last two being sponsors-designate, and Dr. Robert Holmes, Senior Lecturer in Anatomy, Birmingham University.

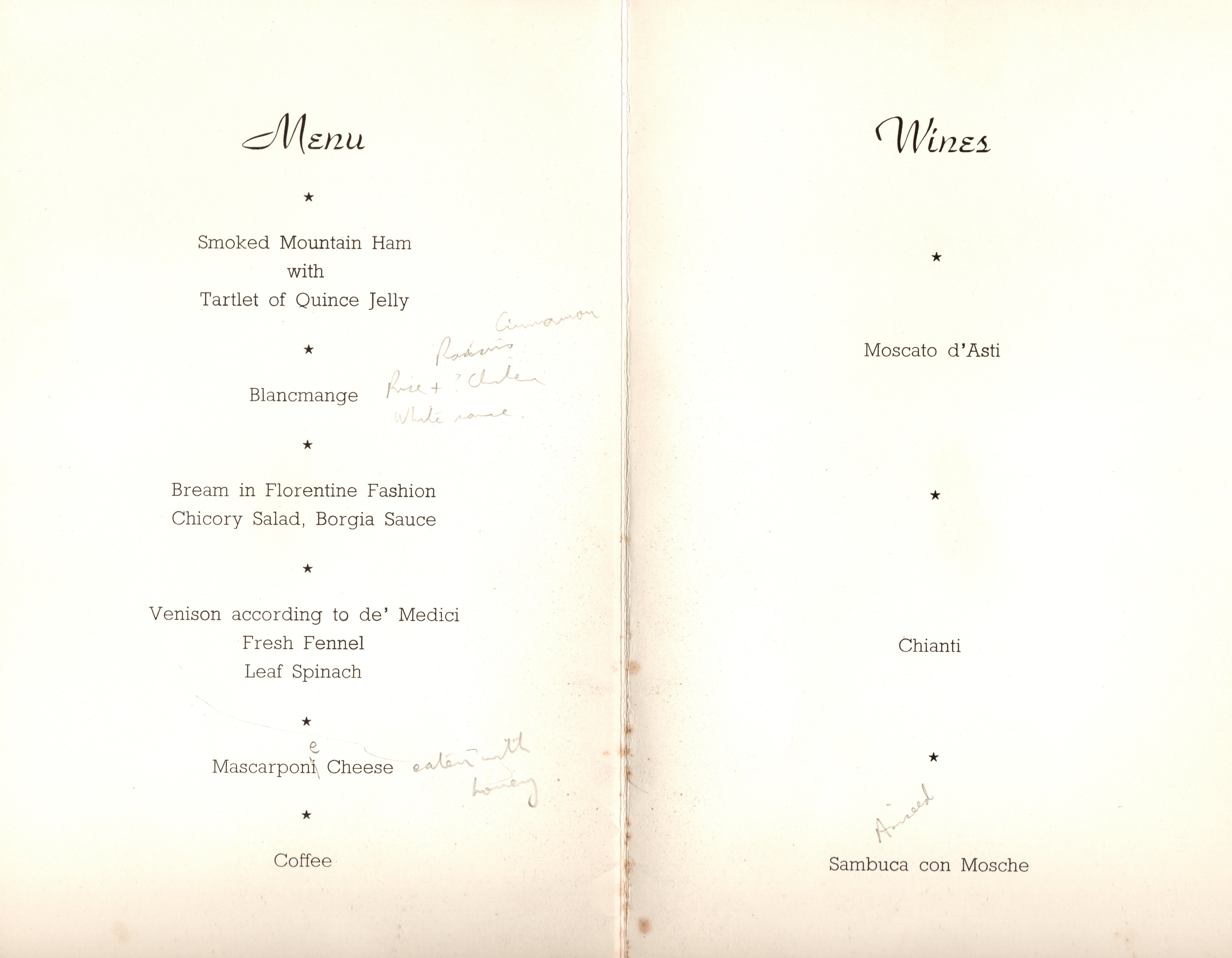

The dinner began with smoked mountain ham, served with tartlets of quince jelly. The quince, the sponsor said, was specified because it was reputed to prevent drunkenness. Renaissance food was probably nasty; still, there was a continuous tradition of pleasure in food in Italy – good, honest, fresh food – the Italians were the last nation to accept the refrigerator. Our dinner was representative of the most vital period of the Italian race; this was how they lived.

Renaissance Italians liked their wine sweet; hence the Moscato with this course.

The second course – sensation – was blancmange. The name, the sponsor explained, covered very various Italian dishes. Ours was a chicken blancmange. The chairman remarked he only wished a certain stern Scottish governess in his past had known this kind.

The sponsor explained why the menu included no pasta, which nowadays so delighted the Italian soul – and his own. It was an innovation of the 19th century. Likewise there was no tomato, for the tomato came in with Garibaldi.

The fish was that unconsidered creature, the freshwater bream, straight from Billingsgate, such as Chaucer’s Franklin had in stew. Florentines were very fond of fish, if truly fresh. Tench was the basic fish for ordinary people and was sold in a market at the end of the Ponte Vecchio. Our bream’s bones were found somewhat treacherous. Its species was the Bronze Bream, but it might have been called the Blue Bream from the language which efforts to skin it had evoked in the hotel kitchen.

It was served with Sauce Borgia – the kitchen’s joke. Sauces were a convenient medium for poison, but the sponsor gave the Borgia Family a generous splash of whitewash. They weren’t half the poisoners they’d been made out to be – unless they had discovered the secret, since lost again, of delayed action poisons, for many of their alleged victims did not die for 8 or 10 days after the suspect dinner. More probably they died of common food poisoning, or of the deadly malaria of the Italian marshes.

Venison, marinated in red wine, was the main course. The sponsor had hoped it could be kid, but in February kid was unobtainable in the course of Nature. The chairman informed the company he did not like venison. Members in general exhibited no repulsion.

Red Chianti was now served. The name, Professor Waterhouse pointed out, has come to cover a great deal of Tuscan wine. Formerly it was limited to a small district of the Chianti hills. Renaissance Chianti was a pretty strong wine, the produce of low, creeping vines, and was drunk ice-cold, “with snow from Vallombrosa or with ice ground to powder” – but not so by us.

“Next “Mascarponi”, a “Florentine” soft white cheese, made from the ingenious sponsor’s own recipe, not with goat’s milk, and served with Hymattus honey.

With the coffee came Sambuca con Mosche, a Florentine liqueur served with a whole coffee bean in the glass, the bean to be chewed as the liqueur was drunk. Most present-day Italian liqueurs, the sponsor said, were introduced in the 19th century and were concocted from herbs more suitable for cleaning the teeth.

After the Chairman’s thanks to Professor Waterhouse, the Club took wine with the Chef, and the sponsor exclaimed: “God bless him!”

… 56 members attended.

A.P. Thomson

13th October 1965