Date: 28th April 2004

Venue: Staff House, University of Birmingham

Sponsor: Alex Hale PhD FSA Scot.

Minutes of a Scottish Lake Dwelling Supper

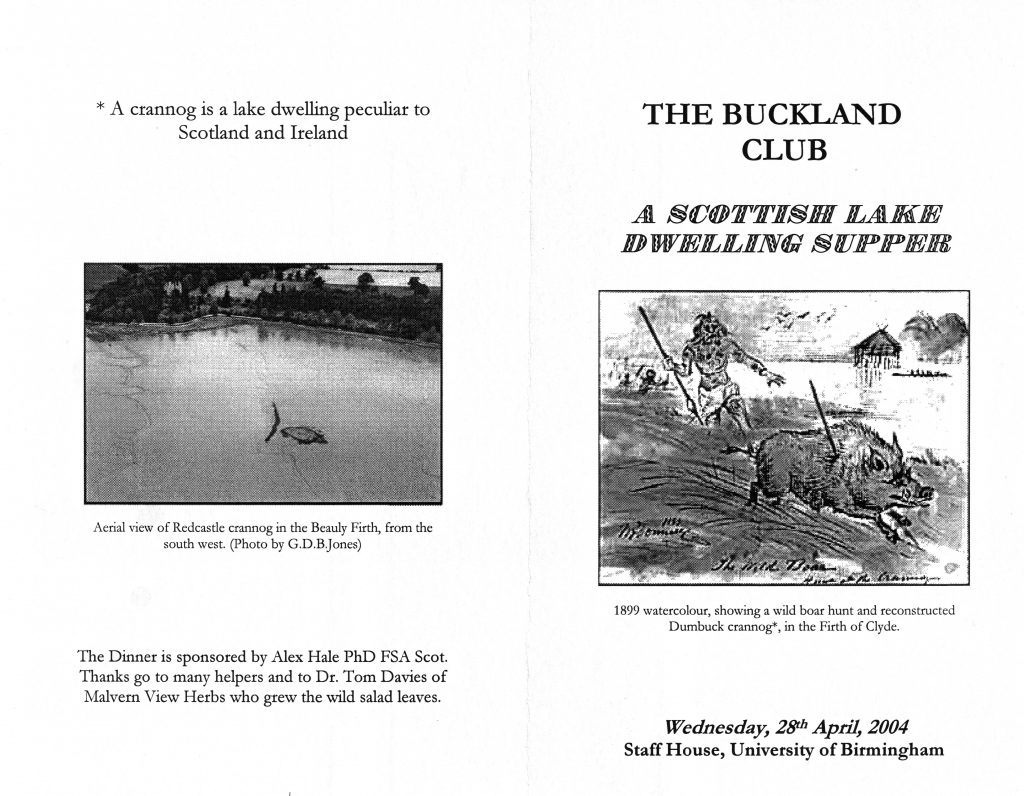

The Club met on the 28th April 2004 to recreate the sort of feast which would have been enjoyed about 2000 years ago by those living in the crannogs of Scotland. Crannogs were big structures, large enough for about 30 people to live under the same roof. In those times, it was not eccentric to live in a loch, but the norm. Practically all fresh water lochs and some coastal lochs in Scotland [and some in Ireland] had their populations of crannog dwellers. One has the impression of social units comprising one extended family per crannog, and there might be a dozen or more other crannogs who would be your neighbours. On Loch Tay there were 19. Most may have been used for living but some may have been places of assembly for ceremonial rites and feasting. Surely we can see here the earliest stirrings of the Scottish clans.

Thanks to the work of archaeologists like our sponsor Dr Alex Hale, much is known about the crannog dweller, his splendid armour and his homestead. There is a troublesome gap, for those planning the dinner: the archaeologists do not know what he ate. From sources such as rubbish dumps, we know something about the ingredients, but his recipes are like that of Green Chartreuse, a secret.

Thanks to the work of archaeologists like our sponsor Dr Alex Hale, much is known about the crannog dweller, his splendid armour and his homestead. There is a troublesome gap, for those planning the dinner: the archaeologists do not know what he ate. From sources such as rubbish dumps, we know something about the ingredients, but his recipes are like that of Green Chartreuse, a secret.

The fishing would be one of the advantages of life on the loch. Our sponsor explained that baskets which were probably used to catch eels have been found and we can be sure that eels would have been a staple. If you caught more than you could eat, or perhaps felt like eating at the time, you would have hung up spare eels and smoked them in the fire in the middle of the crannog for the hungrier times to come. So, smoked eel was a highly likely addition to the diet.

It may be less likely that the canapé was commonly served at cocktail time in the crannog. Undeterred, our sponsor and his father determined that our smoked eel should be served on biscuits. But the biscuits required flour. The seeds of a wild plant called fat hen have been found in and around crannogs. These seeds can be pulverized into flour and thus our Chairman created with pestle and mortar the flour needed for our interesting grey-coloured biscuits. His claim for a repetitive strain injury has yet to be considered by our insurers.

Next, what would crannog man drink? Others may disagree with the proposition, but Dr Hale put forward the hypothesis that the Scots would not be backward in learning about fermentation. Accordingly we began with a glass of pine ale. There is a marketing problem for this fluid: that pleasant but distinctive smell which that the cloakroom has recently been cleaned. However one can say that the pine ale stood up well to the pungent taste of the smoked eel.

Our supper began with Nettle and watercress soup. There was a base of broth, and the flavour of the nettles was excellent. The taste was improved by the knowledge that all nettles had been picked by the ungloved hand of the Chairman. His second claim for compensation is now expected.

Our next dish was pate of wild duck. In 0 AD the locals would have been using flint tipped arrows to take ducks and geese of all species. The pate was served on spelt bread because spelt can be grown in the highlands, having been brought to our shores from the Mediterranean. We drank Cairn O’Mohr Autumn Oak Leaf wine which was fruity and fermented over winter in the barrel. Another wine was Cairn O’Mohr Bramble wine.

Back to the rubbish heap, where animal bones tell us a bit more about crannog man’s supper. The finds show many cattle bones but about 3% are deer. At this time, substantial parts of the Scots native pine had already been cleared so that the land was used for agriculture. But the red deer would have had plenty of pine forest to enjoy and hunting them would have been a group activity if not yet a sport. Once killed, it must have been inevitable that the successful group would have joined together in an evening meal of celebration. The Buckland Club had now become enthusiastic followers in this tradition. We enjoyed braised venison with chanterelle mushrooms in bramble wine with spelt cake. There was also a salad of mixed wild leaves and wild celery.

Our dinner ended with a recipe designed by Dr Hale or perhaps some of his close relatives – Crannog surprise. This was magnificent confection of goats cheese hazel nuts and honey. The ingredients included figs, which were justified by some fascinating archeological research. Following excavations in the Firth of Clyde for Napiers shipyard earlier in the last century, a bag of vegetable matter was retrieved by archeologists. The contents included spelt seeds and two fig pips, but the excavations were never fully written up. The significance of those fig pips may not have been appreciated at the time and it was only recently that an enthusiastic archaeo-botanist recognized what they meant. They would be important evidence of the pattern of trade between crannog settlements and the Mediterranean, a matter of considerable academic interest. And so the radio-carbon dating was performed and proved the fig seeds to date back to: about tea time lst January 1906! Sadly for the trade route theory someone must have dropped a fig roll overboard, shortly before the discovery which led to all this academic excitement.

Archaeologists do not know much about religion in the crannogs, but one body excavated from a stone-lined grave called a Cist was found with the torso wrapped in a shawl made from meadowsweet and within the grave was a large pottery vessel. We may all speculate as to what this means. Our sponsor explained that meadowsweet is used to make mead and the large vessel would have allowed the deceased to drink his mead in the afterlife. On this evidence, Dr Hale advised us to assume that mead which we enjoyed at the end of our meal would also have been used on important celebrations such as this supper, or perhaps to revive first century man on cold dark nights in the crannog. Ours was made in oak barrels, using four pounds of honey per gallon.

The dinner was a triumph of imagination and research on the part of Dr Hale, aided by the Chairman showing reckless disregard for his own safety in the cause of culinary authenticity. The traditions of the Buckland have been most bravely upheld.