Venue: The Barber Institute of Fine Arts & The Staff House, University of Birmingham

Date: Friday 26th October 2007

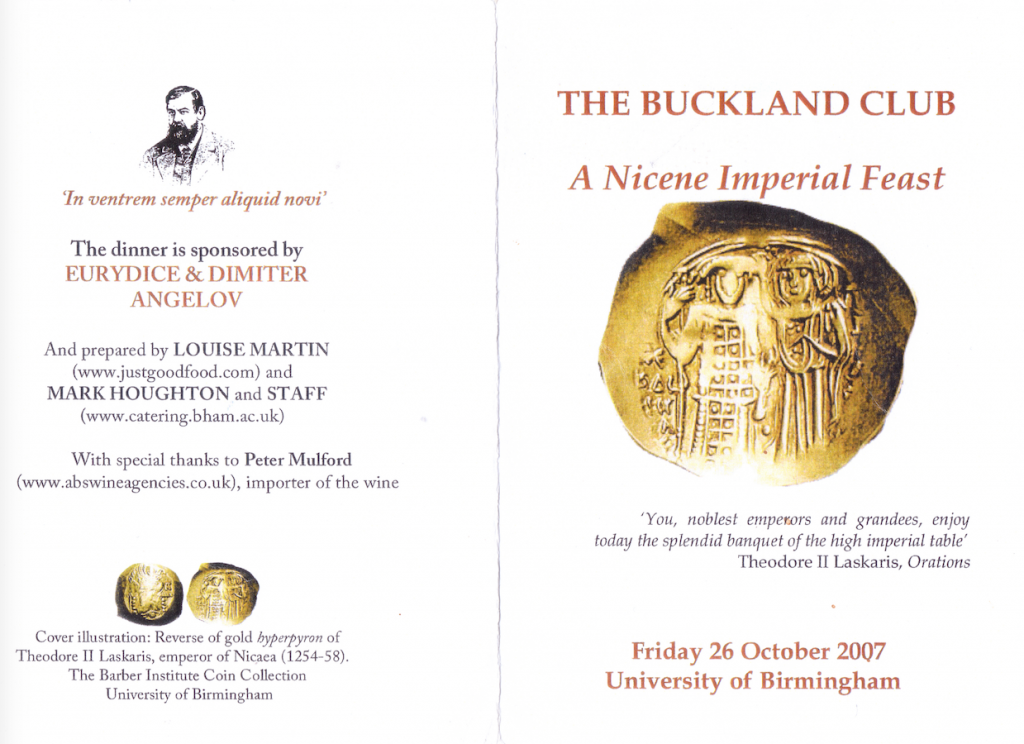

Sponsors: Eurydice & Dimiter Angelov

Invitation to the Dinner

Minutes of A Nicene Imperial Feast

Nicaea is perhaps best known to us, if it is known to us at all, as the venue for the Council meeting that the Emperor Constantine convened in AD 325 to agree the theological status of the Nicene Creed. Although I am sure the assembled bishops at that event would have enjoyed their own version of a Nicene feast, as bishops throughout the ages were wont to do, ours was based on recipes discovered around 900 years later, in the thirteenth century.

A glance at the menu provoked that sense of pleasurable anticipation that precedes any good meal. This was to be a culinary journey to the imperial court of Nicaea, a tiny but formidable empire that blossomed in the thirteenth century in Asia Minor, at a time when the Mongols were wreaking havoc in the East. Nicaea was a small state that had the advantage of being situated near the major trade routes of the time, so that its rulers had access to sugar and spice and well, all things nice – brought from far and wide. Today, we know this area as Iznik, a small town in Turkey.

The honorary host of our banquet was Emperor Theodore II Laskaris, who suffered a tragically early death at the age of 36. We have no evidence of a link to obesity or over-indulgence, but to judge by the contents of our feast this seems a distinct possibility. He may also have over-excited himself with his thirteen-year old wife, but this we shall never know.

Our sponsors for the evening were Eurydice and Dimiter Angelov. Eurydice is Curator of the Barber Institute Coin Collection, and Dimiter lectures in Byzantine Studies in the University of Birmingham.

By a stroke of good fortune, our dinner corresponded with an exhibition in the Barber – Encounters: Travel and Money in the Byzantine World -including two priceless drawings of a fifteenth century Byzantine emperor (John VIII) by the early renaissance artist Pisanello. These were on loan from the Louvre, and Buckland members were regaled with a private view and commentary by Eurydice. A visit to the rest of the Barber collections was offered to those who could be prised from the amuse bouches of caviar and Peloponnese white wine served downstairs.

Strays having been rounded up – at some personal cost – by the wife of our Chairman, the disparate parties then left the Barber, with all the urgency of Shakespeare’s schoolboy, ‘creeping like snail unwilling. . . ’, to the dining room in Staff House, where the feast was to be served.

Our first course featured fresh produce available in autumn across the Balkans and Anatolia: carrots, and cabbage – the latter widely used in medieval Europe because of its anti-inflammatory properties. Olives and a cheese pate (white cheese, myzithra and olive oil) were accompanied by a range of delicious breads, and a white wine from Santorini – which provided the opportunity for a toast to Dimiter and Saint Dimetrios, whose day this was.

Dimiter informed us that the ingredients of our feast were of authentic provenance, the evidence for which he had discovered in Emperor Theodore’s personal correspondence. Theo was a distinguished foodie, though his attitude to food was marked by the contradictory attitudes and views typical of a medieval thinker. On the one hand, he openly expressed his passion for game, fish and wine. On the other hand, he was careful to stress that caring for one’s soul should always take precedence over culinary pleasure. Buckland diners listened attentively…

Our fish Course was fried sturgeon, with watercress salad. Sturgeon came in those days from the Caspian (as did our sumptuous example), and might have been traded as dried fish by Venetian merchants from Constantinople. We learned that cress was also used medicinally – a medieval version of Alka-Seltzer. The sturgeon was accompanied by another Santorini island wine, Boutaris Kallisti Reserve. My impression was that the wines improved as the evening wore on, but then that tends to be one’s general impression after the first four glasses.

There is no record of Theodore’s pursuing pheasant, but we know he hunted cranes and herons with bow and arrow, so why not pheasant? The warm lentil salad and saffron rice proved a noble accompaniment to our game course, as did a wonderfully fresh Skalani wine from the island of Crete.

Theodore’s letters show him to be a lover of cheese, probably of Greek and Turkish provenance. Our yellow cheeses were soft Kaseri, from Greece and a somewhat harder Kefalotyri, from Cyprus, together with a white goat’s cheese from Turkey – all quite delicious. It was a privilege to have such a range of cheese available, and bore witness to the research and sheer effort our sponsors had put, not only into the design but also the sourcing of the feast. It is uncertain whether cheese was eaten with biscuits then, but biscuits (in the form of refined bread) there certainly were. They were widely used in the later Roman Empire and in Byzantium as a food for soldiers, if only because they could be carried long distances without deteriorating. Soldiers would probably not, however, have had access to the noble Samian wine, made from over-ripe Muscat grapes, that we drank with our cheese and dried fruit. It was their loss.

Our final course was baked pears in syrup, cloves and cinnamon, accompanied by strained yoghurt, honey and crushed walnuts – all authentic Nicene fare – accompanied by a 2003 Vinsanto.

Our emperor was a great lover of fruit, in which he saw earthly as well as more spiritual pleasure. He compared, for example, the beauty of black-eyed girls he met on his travels across Asia Minor to the beauty of large pears, leaving to our imagination exactly where he saw the similarity. But equally, not neglecting his spiritual theme, he also spoke of ‘plucking the fruits’ of philosophy from his teacher.

The Royal Feast was an ingenious concept, brought to life by two enthusiastic and deeply knowledgeable researchers with that rare combination of a Bucklandian interest in food and the ability to translate their academic fields of study into a practical menu, which Mark Houghton and his staff delivered, it must be said, with neo-Nicene panache.

Gareth Thomas

Dinner Secretary

February 2008

Menu Card by Roger Hale

Menu Card by Roger Hale