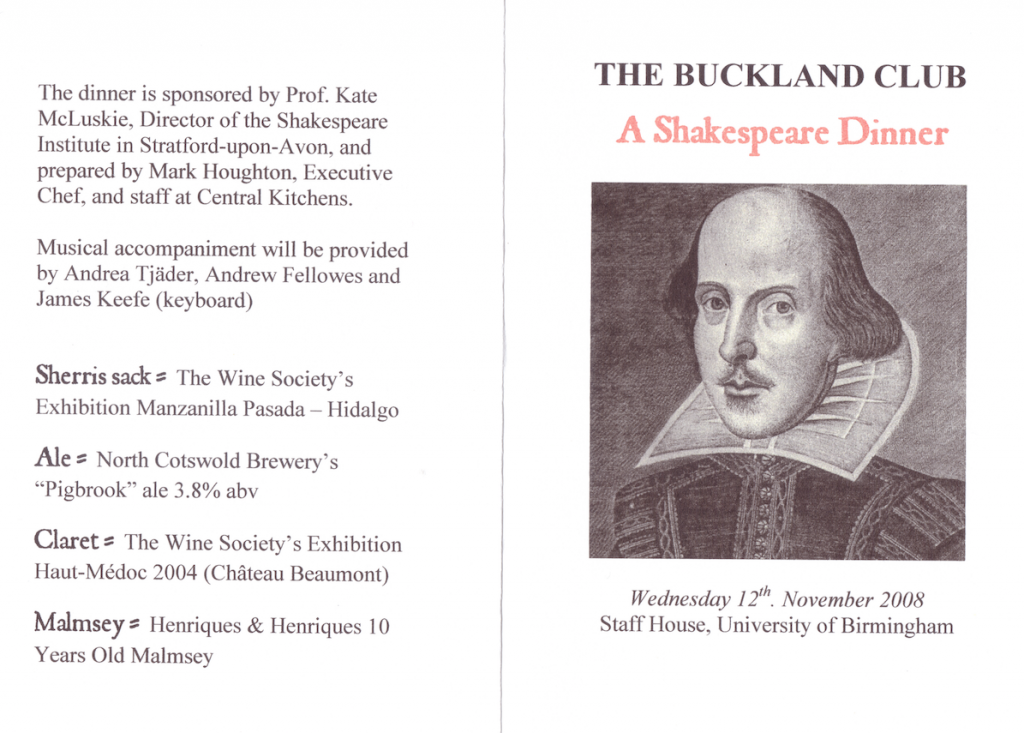

Venue: Staff House, University of Birmingham

Date: Wednesday 12th November 2008

Sponsor: Prof. Kate McLuskie

Below is the flyer sent to members with information about the meal.

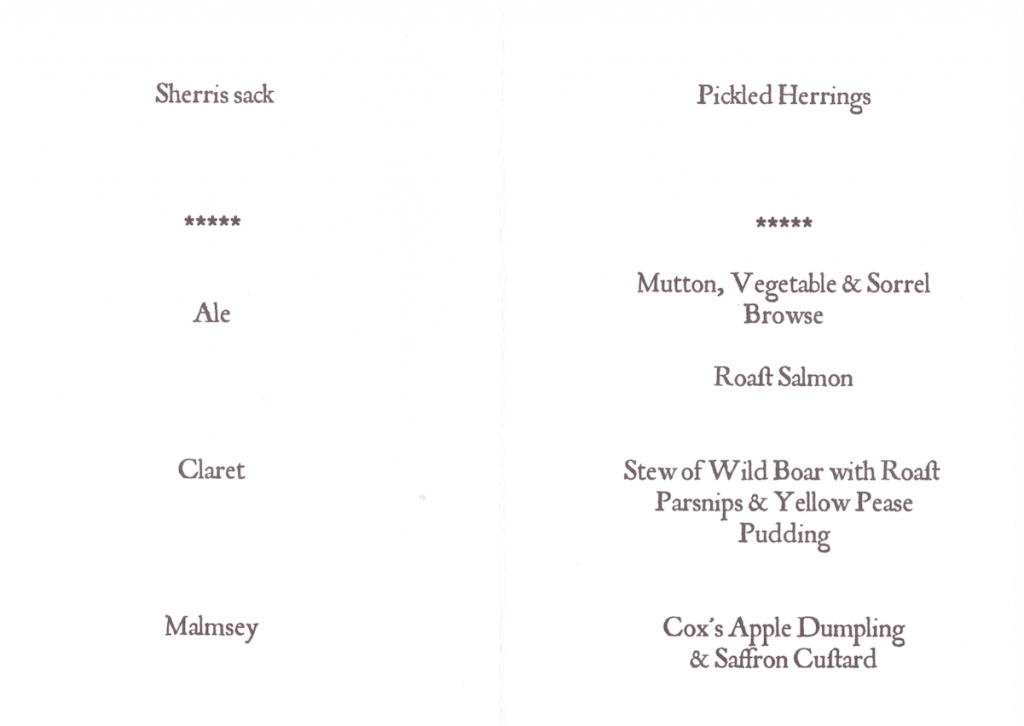

Menu Card

Menu Card

Menu card by Roger Hale

Minutes of the Shakespeare Dinner

This dinner was sponsored by Professor Kate McLuskie, Director of the Shakespeare Institute in Stratford-on-Avon, and in the best Shakespearean tradition our meal was accompanied by songs from his plays, both in the original versions and in twentieth century renditions.

On arrival, members were welcomed with a glass of sherris sack and canapés of pickled herrings. One needs go no further than Falstaff (in King Henry the Fourth, Part Two) to find a spirited eulogy of our aperitif:

“A good sherris-sack hath a twofold operation in it. It ascends me unto the brain; dries me there in all the foolish and dull and crudy vapours which environ it; makes it apprehensive, quick, forgetive, full of nimble, fiery, and delectable shapes; which delivered o’er to the voice, the tongue, which is the birth, becomes excellent wit. The second property of your excellent sherris is the warming of the blood; which before cold and settled, left the liver white and pale, which is the badge of pusillanimity and cowardice; but the sherris warms it, and makes it course from the inwards to the parts extremes….”

Sherris seems to have been constantly on Falstaff’s mind. He says to Bardolph in an earlier play, “Bardolph, get thee before to Coventry, fill me a bottle of sack, our soldiers shall march through, we’ll to Sutton Co’fil.” Falstaff was one of those people who are not entirely convinced that food is essential to a balanced diet.

In Twelfth Night, or What You Will, Sir Toby Belch’s exclamation, “A plague o’ these pickled herring!” is offered as an excuse for what we might politely term an ‘eructation.’ I managed to escape such an embarrassing experience and found the canapés quite delicious, as was the manzanilla pasada.

Our sponsor took as her general theme, ‘moody food.’ In other words, the dramatist used food as a useful device to create opportunities for plot or character development. A banquet is the perfect opportunity to allow tensions and rivalries to surface, and for the cast to interact with each other in a natural way. Characters may sneak out of a banquet to plot, or arrive to interrupt the meal with some momentous piece of news. In the case of the witches around the cauldron in Macbeth, food is used to create a sense of malaise (“eye of newt, and toe of frog, wool of bat and tongue of dog.”), while a pastoral mood might be evoked by evoking a simple piece of fruit, as in Gloucester’s mention of an apple: “Nay, you shall see my orchard where in an arbour we will eat a last year’s pippin of my own graffing….”

The plays of the period give us an interesting insight into the gardens, kitchens, butteries and cellars of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and to experience some of the food grown, prepared and stored there.

Our soup course was a rich lamb stock with minced vegetables, pearl barley and shredded sorrel. The latter, I have discovered in subsequent research, was claimed to “strengthen the seed of man or woman.” It is for you to judge its effect. A basic tenet of the philosophy of food at this time was that, just as individuals were dominated at various times by the four humours (bile, blood, choler and melancholy), so too were individual meats, spices, wines and other foods. Illness resulted from imbalanced humours. Many pottage recipes used peas, spinach and sorrel to give the correct nutritive value to the soup to achieve its medicinal objectives.

The consumption of weak, low-alcohol drinks in Shakespeare’s time has been estimated at one gallon per person per day. Ale – a combination of malt and water – was common. We drank instead a low-alcohol bitter (Pigbrook) from the North Cotswold Brewery. We stopped well short of the gallon, though it was delicious.

The baskets of bread on each table were a reminder of the importance of this staple. Bread flours were milled from wheat, rye or barley and baked into loaves that were regulated by the Assise of Bread. The type of bread consumed reflected the social position of the consumer. Now you may be interested to know that, as Dinner Secretary, I get to see the chef’s detailed notes for the meal. He described our bread as ‘rustic…’

Our roast salmon course was imaginatively accompanied by ginger, cinnamon and crystallised violet petals, plucked no doubt from some magic wood, close by where Lysander slept.

The parade of a magnificent boar’s head for us all to see, gave notice that our meat course was to be a wild boar stew, seasoned to perfection with mace, nutmeg, cinnamon, juniper and – some guessed correctly – black pudding. Roast parsnips and yellow pease pudding were the accompaniment, and the wine was reputable claret, a 2004 Haut-Médoc. The importance of wine and related drinks to our dramatist is reflected in the fact that they are mentioned in 26 out of 37 plays. They include sherris, beer, malmsey and Welsh metheglin. (As an interesting aside, the word metheglin – which is a spiced mead – comes from the Celtic meddygand llyn, meaning‘healing liquor’ – again a medicinal connection which the Welsh have since extended to brandy, whisky and…, well, whatever else happens to be behind the bar.

Our meal was rounded off with a Cox’s apple dumpling, with a stuffing of dried fruits and quince jelly, with saffron custard. Not surprisingly, malmsey was our choice of desert wine.

Our incursion into ‘moody food’ left us with a sense of well-being, as well as a better understanding of the role of food in Shakespeare’s plays. In fact, all was well that ended well.